In May 2025, Cheryl Benard, a former RAND Corporation analyst and wife of Zalmay Khalilzad, a former US negotiator with the Taliban, penned down an article titled “Afghan Refugees Should Not Fear Repatriation,” in which she purposefully argued that Afghanistan is safe for refugees to return to. This reckless assertion, shaped by her “short visits” to the country, dangerously misrepresents the current political landscape of Afghanistan. Her claims distort the truth and contribute to the reproduction of misleading talks on Afghanistan’s ongoing crises.

Before addressing the specific distortions in her recent article, it is imperative to revisit her earlier work on Afghanistan. What initially appears to be a deeply frustrating mischaracterization reveals a consistent and dangerous pattern in her work: that of a privileged/detached outsider and narrative gatekeeper with a clear political conflict of interest.

Cheryl Benard’s recent stances contradict her earlier advocacy: once a prominent critic of the Taliban and an advocate of Afghanistan women. In a 2002 book titled Veiled Courage: Inside the Afghan Women’s Resistance, at a time when Afghanistan was receiving significant international attention following the U.S. invasion in 2001, Benard documented the resilience of Afghanistan women, including the work of the Revolutionary Association of the Women of Afghanistan (RAWA), a grassroots movement founded in 1977.

Among many stories, she included the names of RAWA’s high school members, Nahid and Wajiha, who were killed for their activism. In her own words, Benard described how “urban civil resistance became the domain of women” and praised RAWA for giving “the unique opportunity to observe in real time… how ordinary people are transformed into resistance fighters.” She even noted the Taliban’s treatment of women as “so extreme as to be unique in human history.”

Not surprisingly, she changed her narrative around the same time her husband, Zalmay Khalilzad, became the U.S. Special Representative for Afghanistan. Khalilzad was central to signing the controversial 2020 Doha Agreement, which laid the foundation for the Taliban’s return to power and their establishment of what most of the Afghanistan people describe as an oppressive regime of gender apartheid and persecution. Since then, her writings seem less like neutral analysis and more like a continuation of a political agenda that excuses and justifies the consequences of the Doha Agreement. Today, RAWA lists Zalmay Khalilzad as one of the politicians responsible for Afghanistan’s tragedy, and 76 Afghanistan civil society and human rights organizations have called for his formal prosecution. Around 64 human rights organizations have also called for the prosecution of Benard.

Time and again, she consistently accepts the Taliban’s statements at face value and promotes them through her opinion pieces as though they warrant uncritical public and policy-level trust.

Benard’s departure from her earlier work on women is especially evident in her 2019 article, “Afghan women are in charge of their own faith,” in which she depicted Afghanistan women as passive recipients of Western aid and knowledge. The portrayal aligned with a paternalistic worldview and stripped Afghanistan women of their agency, reinforcing the image of the “white savior” rather than acknowledging our historical struggles. A notable pattern in Benard’s work is her failure to engage with critical feminist scholarship that interrogates how narratives of women’s rights and gender equality in Afghanistan have often been appropriated to serve geopolitical and military agendas. She overlooks the work of scholars such as Lila Abu-Lughod, Saba Mahmood, and Maliha Chishti, who critique the framing of Afghanistan women in terms of “rescue,” “liberation,” and “saving.” Instead, Benard adopts these frameworks wholesale, perpetuating and legitimizing them through her work.

In her recent articles, not only does she exonerate the Taliban’s atrocities, but she also continues to humiliate Afghanistan citizens and trivialize their ongoing suffering. For example, she referred to students of the American University of Afghanistan (AUAF) as “spoiled children of our bad parenting” simply for seeking safety after credible threats to their lives. Just to make her claims more persuasive, she omits the context: the repeated death threats the university received and the 2016 attack, which killed dozens and left many injured. By selectively framing the event, she presents survival as an entitlement for people who had no choice but to escape.

Her portrayal of the Taliban has followed a reverse pattern. She has repeatedly attempted to create a softer image of the Taliban through several rhetorical strategies and selective framing, emphasizing supposed moderation, strategic rationality, and their willingness to distance themselves from Al-Qaeda. However, her arguments have been discredited by the Taliban’s post-2021 policies, as they have instituted a Gender Apartheid regime, maintained ties with Al-Qaeda, and entrenched an autocratic system of governance.

Similarly, in a 2021 article, she urged the international community to believe that the “New Taliban’s” promise of opening girls’ schools was believable, an assurance that has since been proven false. Time and again, she consistently accepts the Taliban’s statements at face value and promotes them through her opinion pieces as though they warrant uncritical public and policy-level trust.

In her latest article, Afghan Refugees Should Not Fear Repatriation, Benard claims, knowing Afghanistan well, an astonishing assertion given that her relationship to the country has largely been that of a “visitor” filtered through privilege and political interest. As someone who was raised in Afghanistan, I would hesitate to make such a claim myself.

Her main argument is that Afghanistan refugees should return to Afghanistan as the country is safe. Her primary source for this claim is a recent personal visit to the country. But why should anyone trust Benard’s brief visit, given her recent history of whitewashing the Taliban and mischaracterizing the realities on the ground over credible reports documenting the ongoing dangers? For instance, in the past few days, four former soldiers were executed by the Taliban in Jawzjan Province upon returning from Iran, and a former female officer in the Afghanistan Republican Army reported that she was gang-raped over two nights while in Taliban detention in Kabul.

She goes further still, portraying Afghanistan immigrants in the United States as burdens who resist integration. The majority of these immigrants are Afghanistan’s highly educated and skilled professionals, including Fulbright scholars, humanitarian workers, and development practitioners. Not to forget, many were allies of the U.S. government who risked their lives to fight terrorism alongside American forces. Some of them and their families have even been victims of anti-migrant sentiments. In April, three Afghan middle school girls were attacked by their peers and hospitalized in the Houston Independent School District. These individuals have fled war and are seeking a chance to live in peace. People like Cheryl Benard contribute to such hostility towards them, put their lives at risk, and fuel xenophobia.

Her other claim that people of Afghanistan receive excessive support from U.S. taxpayers misrepresents the U.S.’s immigration policy and falsely portrays Afghanistan immigrants as dependent on public assistance. In reality, refugees receive assistance through the Reception and Placement Program for three months, after which, they are expected to become self-sufficient. Asylum seekers are not eligible for any of this assistance at all. Afghanistan immigrants are working, paying taxes, and contributing meaningfully to American communities.

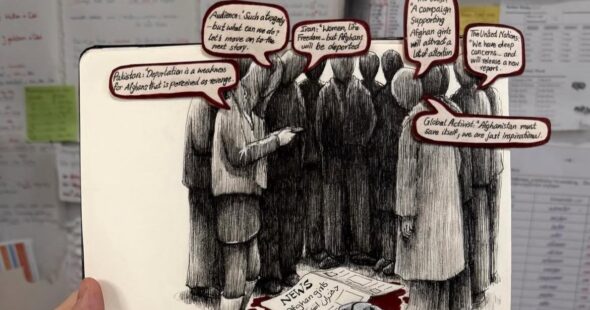

Benard has positioned herself as a knowledge authority on Afghanistan and has built a career interpreting it as she pleases. Her rhetoric is not rooted in solidarity or grounded knowledge but in epistemic violence, privilege, and political interest that have caused real harm.

Benard’s position exemplifies what Fatima Mernissi, Nawal El Saadawi, and Mallica Vajarathon critiqued following the 1976 Wellesley Conference: figures from positions of privilege who assume the authority to interpret for others their conditions, cultures, and experiences. Benard has been doing precisely this. First, as a supposed ally of the women of Afghanistan, and now as a Taliban propagandist, she continues to offer her version of our reality as she pleases.

Her shift is a continuation of epistemic violence, exacerbated by the fact that she carries clear political interests. This shift raises serious questions about her intellectual consistency and political motivations. Since then, it is not the Taliban’s attitude that has changed, but Cheryl Benard’s. Should her claims, then, be taken seriously? While she undoubtedly has a platform, connections, and a broad readership, these alone do not validate her conclusions.

With lives at stake, I urge readers, policymakers, and allies to seek out Afghanistan voices. Listen to independent Afghanistan media. Read the work of scholars and activists who are actually in dialogue with the communities they write about. Do not take the word of someone who, despite her credentials, has demonstrated neither rigorous independent analysis nor respect for the millions of lives under the Taliban totalitarianism.